Across the globe, countries are entering an unprecedented phase of population aging, with some regions experiencing a dramatic decline in birth rates while life expectancy continues to rise. This demographic shift is creating profound social and economic changes, particularly around how societies care for their older citizens.

In the Vietnamese context, the phrase senior living is often synonymous with the nursing home. This narrow association overlooks the fact that globally, senior living is no longer limited to institutional care for the frail. Instead, it has evolved into a vibrant and diverse segment of the real estate industry that integrates healthcare, hospitality, and community design. Senior living today is a dynamic, multidimensional spectrum that encompasses residential options, healthcare services, wellness programs, community engagement, and technological innovations. It is not only about providing shelter or medical supervision; it is about enabling older adults to live independently for as long as possible, to access tailored levels of support when needed, and to remain actively engaged in society.

Senior living is evolving from narrow institutional care into an integrated lifestyle and investment category combining healthcare, hospitality, and community design.

The key to successful senior living solutions lies in understanding the diverse demands of older adults, from those seeking complete autonomy to individuals requiring specialized, intensive care. This approach fosters an environment where aging is not just about safety or medical needs but also about thriving, social connectedness, and holistic wellness. It is within this context that we explore worldwide trends, regional models, and emerging opportunities, with particular attention to the potential within Vietnam’s market.

Market Drivers of Senior Living

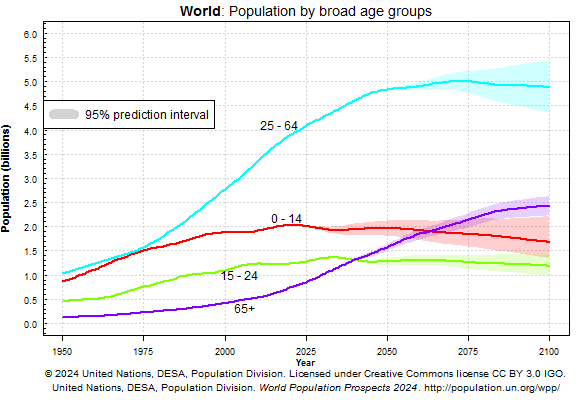

The demand for senior living is primarily driven by five interconnected forces. First and most fundamentally is demographic aging. According to the UN World Population Prospects 2024, the number of people aged 65 and over globally is expected to rise sharply through the 21st century. Additionally, the number of persons aged 65+ is also trending rapidly upward: by the late 2070s, the UN projects there will be 2.2 billion people aged 65 or older globally, a figure that will exceed the number of children under age 18. Asia continues to account for a large share of this growth, with many countries already entering “super-aged” status (20%+ of population age 65+). Japan, for example, already crossed that threshold; other nations such as Singapore and South Korea are close behind. Emerging economies including Vietnam, Thailand, and the Philippines are also experiencing rapid aging due to declining fertility and rising life expectancy, creating increasing pressure on social, healthcare, and real estate systems.

Second, the financial capacity of older cohorts has increased. In developed economies, retirees often hold substantial housing equity, pensions, and savings, enabling them to pay for higher-quality living environments. Even in emerging markets, the rise of a new middle class is creating willingness to pay for comfort and security in later life. A study in rural Vietnam, for instance, found that a substantial share of older persons and their households are willing to use and pay at least partially for community-based care services when these met basic standards of quality.

Third, family structures have changed dramatically. Smaller family sizes and increased labor mobility reduce the availability of unpaid caregiving at home. Vietnam’s average household size has declined from 4.5 persons in 1989 to 3.5 in 2024. This means that more older adults are left without immediate family support, increasing demand for institutional or community-based alternatives.

Fourth, there is growing awareness of wellness and prevention. Senior living is no longer conceived only as a place to manage decline, but as an environment where physical activity, nutrition, and social engagement are actively promoted. Wellness-focused communities, spa-oriented retirement resorts, and intergenerational housing reflect this paradigm shift.

Finally, technology and insurance integration are reshaping the sector. Telemedicine, fall-detection devices, and electronic health monitoring are being embedded into facilities, enhancing safety and efficiency. At the same time, health insurance and long-term care insurance schemes in countries such as Japan, Germany, and Korea provide funding models that make senior living more accessible.

Together, these drivers create a market that is not only expanding but also diversifying. Senior living is moving away from a one-size-fits-all nursing home model towards a spectrum of solutions tailored to different levels of independence, health status, and lifestyle preference.

The Spectrum of Senior Living

Senior living today encompasses a broad continuum of housing and care arrangements, each distinguished by the level of independence afforded to residents, the intensity of care services, and the financial or contractual structure. Drawing on definitions from the Cedar Hill Glossary of Senior Living Terms and recent data from The Senior List (2025), six major segments can be identified.

To highlight the distinctions clearly, the following table summarizes the core differences across segments:

| Model | Typical Resident Profile | Services & Care | Example | Service Cost Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senior Apartments | Fully independent, age-qualified | Housing, minimal amenities, no care | HDB 2-Room Flexi & Community Care Apartments, Singapore (launched 2021–2022 BTO projects like Kallang/Whampoa) | Low |

| Independent Living | Active, healthy retirees | Meals, transport, activities, recreation | Sunway Sanctuary, Malaysia (opened 2023, independent living suites with wellness focus) | Low-Moderate |

| Assisted Living | Semi-independent, need ADL help | Daily living support, communal dining, staff | ReU Living – MiCasa Retirement & Recovery Village, Kuala Lumpur (opened 2022), Perennial Assisted Living (Singapore, 2026) | Moderate |

| Memory Care | Dementia/Alzheimer’s patients | Secure environment, dementia-trained staff | De Hogeweyk Dementia Village, Netherlands (2009, still global benchmark) | Moderate-High |

| Nursing Homes | Frail, high medical needs | 24/7 nursing, rehab, clinical oversight | Perennial Living @ Kovan, Singapore (opening 2026, with 100-bed nursing wing) | High |

| Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs) | Mixed, aging in place | Continuum: independent → skilled | Kampung Admiralty, Singapore (completed 2018, integrated housing + medical + social care); U.S. CCRCs like The Clare, Chicago | High + entrance fee |

Senior living has also evolved into variations beyond the main models. Luxury senior apartments cater to affluent retirees with concierge services, wellness programs, and resort-like amenities, while palliative and hospice care provide comfort and dignity at the end of life, often through dedicated facilities or home-based support. Other hybrids such as assisted living communities with memory care units or CCRCs that include dementia neighborhoods, show how providers adapt traditional models to meet more specialized needs.

Vietnam in the Global Senior Living Context: Demand, Supply, and Emerging Opportunities

The global senior living market reveals sharp contrasts between developed and emerging economies. In advanced markets such as Japan, Singapore, the United States, and Europe, demand is already mature, driven by “super-aged” demographics, smaller households, and strong financial capacity. Seniors in these countries often expect to live independently from their families and have access to robust pension or long-term care insurance schemes that subsidize costs. As a result, demand is diversified across the full continuum. Choice, quality of life, and specialization, particularly in dementia and palliative care, are central priorities.

By contrast, in emerging economies like Vietnam the situation is more transitional. Family-based care remains the cultural norm, but urbanization and migration are steadily eroding traditional multigenerational households. At the same time, willingness to pay for private services is still constrained. Research has found that demand for full-cost services remains very low. This underscores that affordability, not just availability, is the primary barrier.

Accelerating aging, limited supply. Bridging tradition with innovation. Early movers can define Vietnam’s senior living future.

A noteworthy regional signal for Vietnamese consumers is the rise of luxury senior living in Malaysia - a short-haul, culturally proximate market - where resort-style independent and assisted communities are expanding, targeting both locals and international retirees/long-stayers on medical-wellness packages. This cross-border benchmark subtly influences expectations in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi regarding what “good” senior living can look like.

Supply in Vietnam remains thin and fragmented. At present, the market is dominated by small-scale nursing homes, religious or charity-run care centers, and isolated pilot projects. A handful of private initiatives, such as Les Hameaux de l’Orient and Kien Nam Senior Living Resort in Cu Chi, have introduced a more “resort-style” concept, while large developers like Vingroup and Sun Group have recently announced plans to enter the senior living and healthcare space. However, these projects remain early-stage exceptions. Even with Vingroup’s recent launch of an international-standard senior living community, Vietnam has yet to develop a fully established ecosystem spanning senior apartments, assisted living, and memory care as seen in developed markets.

The result is a widening supply-demand gap. On the one hand, demographic aging in Vietnam is accelerating rapidly. On the other hand, current supply lacks both scale and diversity, and public systems such as long-term care insurance do not yet exist. The challenge is not simply to import models from advanced economies, but to adapt them to Vietnam’s social and cultural realities.

The opportunity, therefore, lies in bridging tradition and modernity: creating affordable, community-based senior living solutions that respect the role of family while integrating professional standards of care. Hybrid models such as assisted living apartments with optional service packages, day-care centers linked to local communities, or senior housing embedded in larger mixed-use developments, can deliver both accessibility and dignity. For investors and policymakers, this represents a chance to shape a new asset class at an early stage, one that balances affordability with innovation and responds directly to the needs of a rapidly aging society.

REFERENCES

1. United Nations, World Population Prospects 2024.

2. Le Van Hoi et al (2012). Willingness to use and pay for community-based elder care services in rural Vietnam. BMC Health Services Research.

3. General Statistics Office of Vietnam, Press release on the results of the 2024 population living standards survey.

.

Author & Contact Information

Ms. Linh Nguyen

Director – Da Nang Branch

MOF Valuer

📩 linh.nguyen@dcfvietnam.com

📞+84 763 30 44 30